Multiplexed DNA-functionalized graphene sensor with artificial intelligence-based discrimination performance for analyzing chemical vapor compositions | Microsystems & Nanoengineering

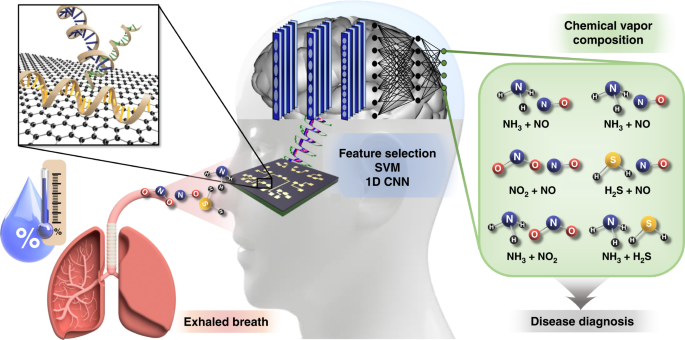

The process of diagnosing lung and liver diseases using exhaled breath is illustrated in Fig. 142,43. The chemical vapor mixture under humid conditions is released from the exhaled breath of humans. We injected NH3, NO, NO2, and H2S under low- and high-humidity conditions. These chemical mixtures were verified by our graphene-based ssDNA sensor array and output as an electrical signal, which was used to identify the mixed state of the chemical vapor composition through artificial intelligence via feature selection, SVM, and 1D CNN. Based on these results, diseases such as asthma, liver diseases, kidney diseases, stomach ulcers, and duodenal ulcers can be diagnosed7,8,9,10,11,12.

Schematic diagram of the process of diagnosing diseases by sensing constituent chemical vapors of exhaled breath through a multiplexed DNA-functionalized graphene sensor and identifying gases through artificial intelligence. NH3, NO, NO2, and H2S molecules that exist individually or in mixed states in exhaled human breath (under conditions of considerable humidity) are detected by the gas sensor array to which the DNA sequence is applied; the presence of these molecules is conveyed through an electrical signal. Their identification is achieved through artificial intelligence via feature selection, support vector machine (SVM), and 1D CNN for the diagnosis of lung and liver diseases. Adapted with permission42,43

Schematic diagram of the process of diagnosing diseases by sensing constituent chemical vapors of exhaled breath through a multiplexed DNA-functionalized graphene sensor and identifying gases through artificial intelligence. NH3, NO, NO2, and H2S molecules that exist individually or in mixed states in exhaled human breath (under conditions of considerable humidity) are detected by the gas sensor array to which the DNA sequence is applied; the presence of these molecules is conveyed through an electrical signal. Their identification is achieved through artificial intelligence via feature selection, support vector machine (SVM), and 1D CNN for the diagnosis of lung and liver diseases. Adapted with permission42,43

Design and fabrication of a gas sensor array

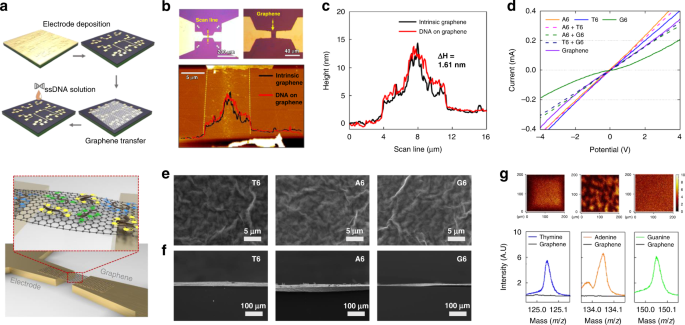

The sensor array was fabricated using monolayer graphene. Prior to fabrication, graphene should be functionalized by employing one of the following characteristics: nanoparticles, DNA, and organic materials34,36. First, we functionalized graphene using ssDNA and subsequently fabricated a sensor array, which exhibited increased reactivity to the gas through the implementation of DNA. In addition, this method of preparation offers certain advantages, such as simple synthesis and sensor array production based on the DNA sequence. Six graphene-DNA sensors and one pristine graphene sensor were fabricated; the DNA sequences AAA-AAA (A6), TTT-TTT (T6), and GGG-GGG (G6) were utilized for this purpose. Three sensors were used for the A6, T6, and G6 sequences, and three sensors were thereafter constructed by utilizing the A6T6, A6G6, and T6G6 sequences. The sensor fabrication process is illustrated in Fig. 2a.

a Schematic of the fabrication process of the graphene-DNA gas sensor array and conductive channel. b Optical and AFM images of the gas-sensing channel. c The height difference between AFM measurements before and after ssDNA adsorption was 1.61 nm. G peak (d) of Raman shift. e Top-view SEM images of graphene using functionalized thymine, adenine, and guanine sequences and cross-sectional-view SEM images (f) of graphene using functionalized thymine, adenine, and guanine sequences. g Mapping TOF-SIMS image of graphene using functionalized thymine, adenine, and guanine sequences, showing the magnitude spectral peaks at masses of 125 (thymine), 134 (adenine), and 150 m z−1 (guanine)

a Schematic of the fabrication process of the graphene-DNA gas sensor array and conductive channel. b Optical and AFM images of the gas-sensing channel. c The height difference between AFM measurements before and after ssDNA adsorption was 1.61 nm. G peak (d) of Raman shift. e Top-view SEM images of graphene using functionalized thymine, adenine, and guanine sequences and cross-sectional-view SEM images (f) of graphene using functionalized thymine, adenine, and guanine sequences. g Mapping TOF-SIMS image of graphene using functionalized thymine, adenine, and guanine sequences, showing the magnitude spectral peaks at masses of 125 (thymine), 134 (adenine), and 150 m z−1 (guanine)

Graphene-ssDNA-based gas sensor arrays were fabricated through the following three steps: (i) electrode deposition, (ii) graphene deposition and patterning, and (iii) ssDNA functionalization. The sensor array was fabricated using SiO2 (1 μm)/Si (500 μm) wafers through a mass production process. A 100-nm-thick electrode was molded via photolithography and Au sputter deposition, as depicted in Fig. 2a. The graphene deposited through chemical vapor deposition was patterned between the Au electrodes via photolithography and an O2 plasma process. After annealing, the ssDNA was functionalized using droplets under 100% relative humidity for 3 h. The fabricated sensor arrays were 15 mm × 15 mm in size. The formation of monolayer graphene was confirmed through Raman analysis before and after annealing, and the peak intensity ratio of 2D to G was 1.73 (I2D/IG) (refer to Figure S1). In addition, optical and atomic force microscopy (AFM) images are presented in Fig. 2b. Graphene binds to s-DNA through π–π stacking, and after ssDNA binding, the adsorption of ssDNA onto graphene based on the differences in height was confirmed through AFM measurements (refer to Fig. 2c)44,45. The current–voltage (I–V) characteristics of the changed sensor array, which confirmed the functionality of the ssDNA in the graphene, are plotted in Fig. 2d40,46. The binding of ssDNA is evident in the top and cross-sectional views of the SEM images (refer to Fig. 2e, f). In addition, a time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) analysis was conducted to confirm the sequencing of the sensor array (refer to Fig. 2g). Thus, the DNA sequences of thymine, adenine, and guanine exhibited nucleic acid peaks of 125 (C5H5N2O2−), 134 (C5H4N5−), and 150 (C5H4N5O−), respectively47. Furthermore, the proper implementation of the sensor array was confirmed through the results of a mass peak analysis according to the ssDNA mixture of the formed sensor array (Figs. S2–S7). The sequence configuration of the graphene ssDNA sensor array for sensing gases under low- and high-humidity conditions is presented in Fig. 3a; the results demonstrated that the ssDNA chemically doped the graphene through a change in the G peak of the Raman spectra of graphene after ssDNA binding; thus, the sensor array was properly implemented (refer to Fig. 3b–f).

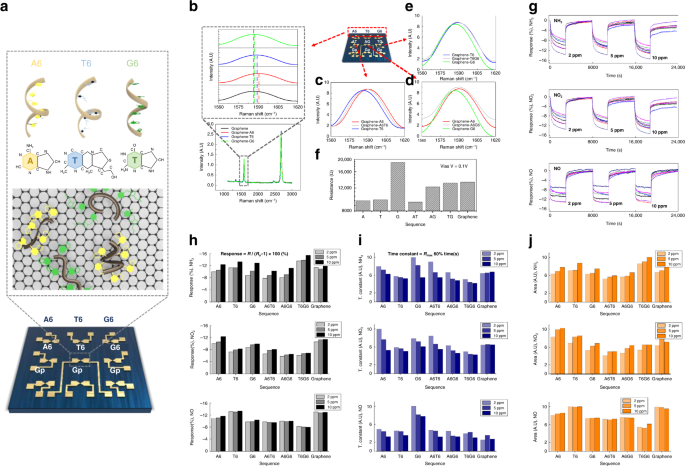

a DNA sequence and placement applied in the graphene-DNA gas sensor array for sensing gases under low- and high-humidity conditions and G-peak shifts of Raman spectra according to DNA sequences of b A6, T6, G6, c A6T6, d A6G6, and e T6G6. f Resistance according to the bias (V) of the sensor array channel. The g response, h maximum reactivity, i time constant, and j area used as the response toward NH3, NO2, and NO gases at 2, 5, and 10 ppm, respectively

a DNA sequence and placement applied in the graphene-DNA gas sensor array for sensing gases under low- and high-humidity conditions and G-peak shifts of Raman spectra according to DNA sequences of b A6, T6, G6, c A6T6, d A6G6, and e T6G6. f Resistance according to the bias (V) of the sensor array channel. The g response, h maximum reactivity, i time constant, and j area used as the response toward NH3, NO2, and NO gases at 2, 5, and 10 ppm, respectively

The measurement conditions for the target gas under dry conditions are listed in Table S1. For all three types of individual gases, the three mixed gases were measured for three distinct concentrations: the NO2, NO, and NH3 gases were measured at 2, 5, and 10 ppm, respectively, and the mixed gas was measured by varying the mixture ratio.

The 1:1 mixing ratio was measured at 2, 5, and 10 ppm and was optimized at 10 ppm. Consequently, a concentration of 10 ppm was kept constant for mixing ratios of 2:1, 1:2, 3:1, and 1:3. The individual gases were measured three times for each concentration, and the mixed gas was measured nine times per mixing ratio. The gas measurement was performed for 368 s and had a recovery time of 114 s. Our sensors detected small concentrations of gas with a fast response and recovery time (refer to Table S2)15,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81. The reactivity of the graphene-ssDNA gas sensor array for NH3 and NO2 is presented in Fig. 3g–j.

The seven-sensor array exhibited a reactivity of approximately 5–7.8% for NH3 gas; notably, the reaction rate increased with an increase in concentration (refer to Fig. 3g). A sensor consisting of a combination of ssDNA T6 and G6 with an NH3 concentration of 10 ppm exhibited a reactivity of approximately 15%. In contrast, the response of the sensor array with NO2 (refer to Fig. 3h) exhibited a slightly lowered response of 5–12%, whereas the array comprising the DNA sequence demonstrated the highest reactivity with a response of approximately 12% with a graphene-A6 sequence. According to the difference in reactivities, data from a pristine graphene sensor suggested a diminished performance under an in situ change in concentration and selectivity compared to that of a DNA-functionalized sensor, at approximately 10% for NH3 and NO2. Generally, the sensor array can contribute to the improvement in selectivity by varying its reactivity for each gas82,83. The ssDNA-functionalized sensor had an improved selectivity for these two gases via graphene functionalization. In addition to the responsiveness of the sensor array, different features of the sensor array can be applied for gas discrimination (refer to Fig. 3i, j). The time constant is a feature related to the reaction diagram, and the area is a feature related to the reaction rate and reactivity. Evidently, the extracted features from the sensor data exhibit selectivity depending on the type of gas, which improves the classification rate for the determination of a specific gas type. Thereafter, to determine the mixed gas composition, the gas mixture ratios were measured. For a mixing ratio of 1:1, the sum of the two gas concentrations was measured at 2, 5, and 10 ppm, and the reactivity gradually improved as the concentration increased. According to the data, the reactivity changed slightly according to the mixing ratio; this trend is identical to that observed for the PCA plot. However, no obvious difference in reactivity was observed. We chose to use artificial intelligence for analysis to address this issue.

The measurements of NH3 and H2S were conducted under humid conditions to determine the applicability of the sensor in breath analyzers. In an environment similar to that of exhaled breath (80% humidity), individual gas measurements at concentrations of 2, 5, and 10 ppm were repeated three times for 368 s with an air recovery time of 114 s. Mixing ratios of 1:1, 1:3, and 3:1 were measured nine times at a concentration of 10 ppm to discriminate between the gas species under humid and dry conditions. Consequently, compared to those under dry conditions, we obtained an improved reactivity for NH3 (20–32%) and H2S (20–40%) under humid conditions. As with the data under dry conditions, these data were also analyzed using artificial intelligence.

Chemical vapor discrimination with feature selection

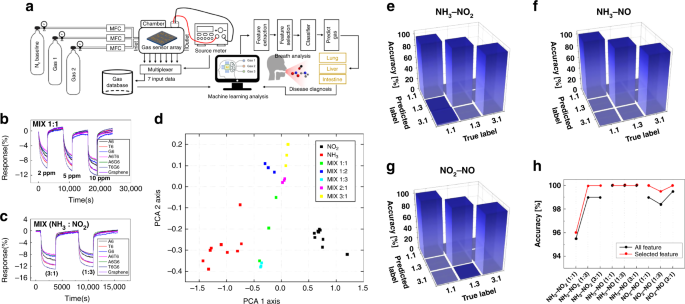

The incorporation of appropriate features significantly positively impacts the performance of a machine learning model84,85. A machine learning model possesses fewer hyperparameters than a deep learning model. Therefore, to fine-tune this hyperparameter and obtain the best performance, features with minimum dimensions should be extracted while maintaining as much of the data as possible. The features extracted from the response data of the gas sensor array should be representative, exhibit appropriate physical and chemical significance, and be able to account for the correlation between data points. In this study, we used the Boruta algorithm for feature selection (refer to Figure S15); the dimensions of the extracted features were reduced by using this technique, and it was subsequently applied for classification. The process of sensing the mixed gas and discriminating the gases with feature selection is illustrated in Fig. 4a. To analyze the effect of the feature selection technique, support vector machine (SVM) analysis was conducted by implementing the extracted features without feature selection; the results of feature selection were generally higher than those without such an application.

Schematic diagram (a) for gas data acquisition and gas species identification. b Mixed gas at a 1:1 ratio of NH3 to NO2 and c data at mixture ratios of 1:3 and 3:1. d PCA plots after feature extraction: the data exhibit a constant degree of dispersion for the mixed gas. Confusion matrix for e NH3–NO2, f NH3–NO, and g NO2–NO mixed gases after feature selection. h Comparison of the classification rate of the Boruta algorithm with feature selection and SVM analysis without feature selection under conditions of low humidity

Schematic diagram (a) for gas data acquisition and gas species identification. b Mixed gas at a 1:1 ratio of NH3 to NO2 and c data at mixture ratios of 1:3 and 3:1. d PCA plots after feature extraction: the data exhibit a constant degree of dispersion for the mixed gas. Confusion matrix for e NH3–NO2, f NH3–NO, and g NO2–NO mixed gases after feature selection. h Comparison of the classification rate of the Boruta algorithm with feature selection and SVM analysis without feature selection under conditions of low humidity

Some errors in the form of noise may occur during gas measurements for several reasons, and we applied the filter for correction. First, ambient white noise may be introduced into the measurements. Second, noise occurs owing to the processes pertaining to the gases in the chamber, such as desorption during the adsorption process or adsorption during the desorption process between gas measurements. Third, noise occurs owing to the time difference of the input voltage in the multichannel switching device during sensor array measurement. Fourth, thermal noise is generated by the heaters used in the metal oxide gas sensor, which is introduced into the measurements. Finally, discrete reactions occur for certain gases in certain types of sensors. Therefore, we employed the filtfilt function in the Python 3.7 package SciPy 1.4.1, which is a forward-backward filter for correcting such noise. This linear filter achieves zero-phase filtering by applying an infinite impulse response filter twice—once forward and once backward. All the hyperparameters in the filtfilt function were optimized. The results of the filter were as follows: We extracted a total of 840 features to increase the recognition rate for gas species, with 120 features for each of the seven sensors. The feature sets included the magnitude, derivative, difference, time constant, and area under the graph; these feature sets are listed in detail in Table S3. The magnitude included the maximum absolute value, which can be the maximum or minimum magnitude depending on the selectivity performance of the sensor, downsampled values of the magnitude, and downsampled values of the normalized magnitude. The derivative included the maximum and minimum derivatives of the graph, downsampled values of the derivative, and maximum and minimum second derivatives during both the injection and purging stages. The differences were calculated on the basis of five intervals (two in the reaction stage and three in the purging stage). The time constant and area were calculated for eight intervals (four in the reaction stage and four in the purging stage), and the time constant was calculated based on the start and end points of each reaction. However, in the MDFG data, certain features exhibited minimal selectivity for certain gases, and certain data were more noise-like than those of the reactions. These characteristics prevented our feature extraction algorithms from performing effectively. Therefore, we set the feature value of the low-quality data to zero; this irrelevant feature was removed during the feature-selection stage.

Feature selection is an essential technique for machine learning. By eliminating highly correlated, irrelevant, and noisy features, the occurrence of overfitting is reduced, and the performance of the model is improved by minimizing the variance and maximizing the generalizability of the model. The efficiency of this algorithm can be further improved by reducing the operation time and computational load during feature selection. We considered three types of mixed gases with various mixing ratios, namely, NO2–NH3, NO–NH3, and NO–NO2, with mixing ratios of 1:1, 1:3, and 3:1 under low-humidity conditions. The gas response data from the sensor array, which are depicted in Fig. 4b and c, were input to the model, and the model output the mixture ratio. The principal component analysis (PCA) results for NO2–NH3 mixed gas are illustrated in Fig. 4d. The results were obtained after optimization of the hyperparameters, such as the percentile using the Boruta algorithm and soft margin parameter using an SVM. According to the Boruta algorithm with feature selection, for the NO2–NH3 mixture, the average optimal number of selected features was 102.73. In addition, the compression ratio was 7.01. The classification accuracy from the Monte Carlo cross-validation (MCCV) was 98.67%. For the NO–NH3 mixture, the average optimal number of selected features was 155.79. Moreover, the compression ratio was 4.62, and the classification accuracy of the MCCV was 100%. Finally, for the NO–NO2 mixture, the average optimal number of selected features was 119.6, the compression ratio was 6.02, and the classification accuracy of the MCCV was 99.33%. Confusion matrices of the classification accuracy for each gas mixture are illustrated in Fig. 4e–g and provided in Table S4. The results of SVM analysis using the extracted features without feature selection, such as the precision, recall, and f1 score, are provided in Table S5 with the results of classification with feature selection. The classification rate increased after feature selection, and a considerably high recognition rate was obtained, as depicted in Fig. 4h.

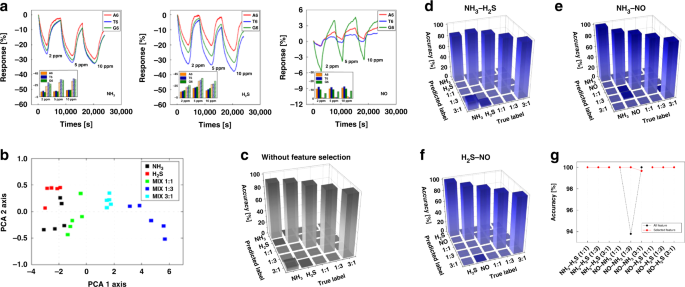

We considered five types of mixed gas, NH3–NO, NH3–H2S, and H2S–NO, with three mixed gases with mixing ratios of 1:1, 1:3, and 3:1, and two individual gases under high-humidity conditions, as depicted in Fig. 5a. The PCA and SVM analysis results for the NH3 and H2S mixed gas are illustrated in Fig. 5b and c. A comparison of the classification accuracy of the two algorithms is provided in Table S6 and Fig. 5g, and the results of feature selection under high-humidity conditions indicated higher accuracy than SVM analysis with low-humidity conditions. Therefore, we confirmed that our Boruta algorithm using feature selection for gas mixture discrimination performed better than the SVM analysis using only extracted features. According to these results, our machine learning-based feature selection algorithm can discriminate gas mixtures with high accuracy and offers high performance in high-humidity conditions, which suggests that it can be effectively applied in exhaled breath analyzers for the diagnosis of diseases.

a Reactivity for individual gas molecules of NH3, H2S, and NO at 2, 5, and 10 ppm and enhanced responses through FG-ssDNA under humid conditions. The bar with the dashes shows the reactivity in the case of 80% humidity, where an approximately 2 to 2.5 times higher reactivity is observed. Result of the subsequent b PCA and c result of SVM analysis for NH3-H2S mixed gases. The confusion matrix for d NH3-H2S, e NH3-NO, and f H2S-NO mixed gases after feature selection under conditions of high humidity. g Comparison of the classification rate of the Boruta algorithm with feature selection and SVM analysis without feature selection under conditions of high humidity

a Reactivity for individual gas molecules of NH3, H2S, and NO at 2, 5, and 10 ppm and enhanced responses through FG-ssDNA under humid conditions. The bar with the dashes shows the reactivity in the case of 80% humidity, where an approximately 2 to 2.5 times higher reactivity is observed. Result of the subsequent b PCA and c result of SVM analysis for NH3-H2S mixed gases. The confusion matrix for d NH3-H2S, e NH3-NO, and f H2S-NO mixed gases after feature selection under conditions of high humidity. g Comparison of the classification rate of the Boruta algorithm with feature selection and SVM analysis without feature selection under conditions of high humidity

Chemical vapor discrimination with 1D CNN

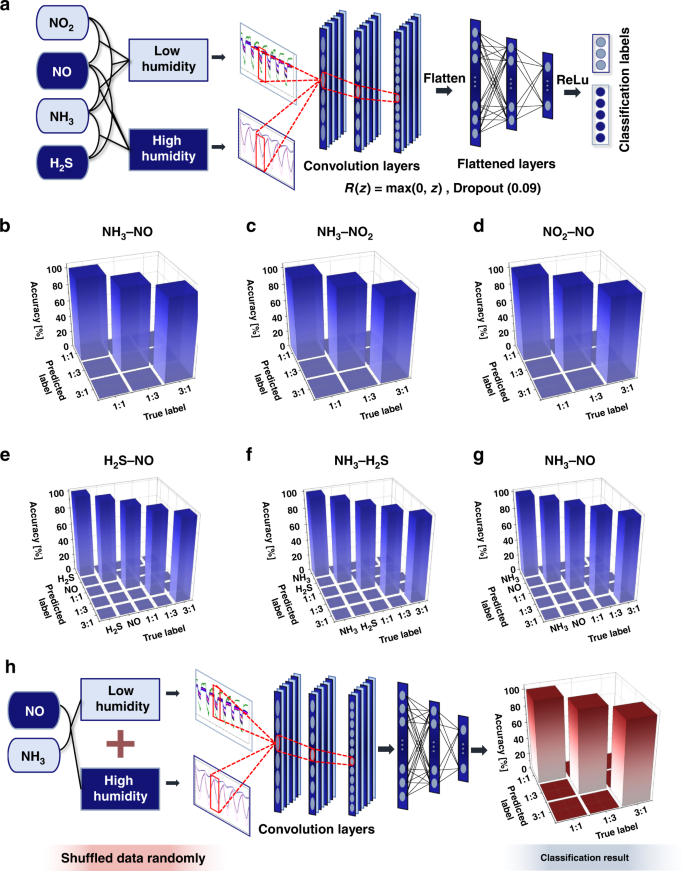

The gas classification results of the machine learning algorithm through feature extraction and the SVM method were almost perfect; nevertheless, in this study, we designed a deep learning algorithm by employing a 1D convolutional neural network (CNN) for completely automated and rigorous mixed gas classification86. For the electrical signals of the experimental gas sensor array, 1D CNN models were designed for conditions of high and low humidity; these models were trained and tested for each mixed gas because the number of classes for classifying each humidity condition was different. For the low-humidity condition model, three classes of classification were performed with mixing ratios of 1:1, 1:3, and 3:1 for each mixed gas combination of NH3–NO, NH3–NO2, and NO2–NO. For the model under high-humidity conditions, five classes of classification were performed with two individual gases, and the mixing ratios for each mixed gas combination of NH3–NO, NH3–H2S, and H2S–NO were 1:1, 1:3, and 3:1.

Because the height of the data was not considered for the classification of the types and proportions of the mixed gas, the height of the data was unified to 1 through normalization, and the data were augmented with noise because the volume of experimental data for training was considerably small. The data were randomly split into a training set and test set at a ratio of 2:1 for all experimental conditions.

A schematic of the common structure of the models for low- and high-humidity conditions is presented in Fig. 6a. In the high- and low-humidity models, the processed data were input into a 1D convolution layer with a sensor array as the channels, and after three sets of convolution, activation, and dropout, the data were normalized. Then, the normalized data were input into a linear layer sequence, with three sets of linear, activation, and dropout41,86,87. The designed 1D CNN model was trained by repeating 20 epochs by inputting the training set, and the model was optimized through logit and loss functions. As the training loss converged to 0 for a learning rate of 0.001, the results confirmed that our model was trained well with the experimental data. We checked our model performance by inputting the test set into the trained model, and the test loss converged to 0, which was similar to that observed for the training loss.

a 1D CNN-based deep-learning structural schematic for gas classification. Confusion matrices for classification results of b NH3–NO, c NH3–NO2, and d NO2–NO mixed gas under low humidity conditions and at mixing ratios of 1:1, 1:3, and 3:1. Results of e H2S–NO, f NH3–H2S, and g NH3–NO mixed gas under conditions of high humidity and individual gas at mixing ratios of 1:1, 1:3, and 3:1. h NH3-NO mixed gas 1D CNN classification result for data randomly shuffled with humidity conditions

a 1D CNN-based deep-learning structural schematic for gas classification. Confusion matrices for classification results of b NH3–NO, c NH3–NO2, and d NO2–NO mixed gas under low humidity conditions and at mixing ratios of 1:1, 1:3, and 3:1. Results of e H2S–NO, f NH3–H2S, and g NH3–NO mixed gas under conditions of high humidity and individual gas at mixing ratios of 1:1, 1:3, and 3:1. h NH3-NO mixed gas 1D CNN classification result for data randomly shuffled with humidity conditions

The evaluation results of our 1D CNN model on the test set are presented as confusion matrices and illustrated in Fig. 6b–d under low-humidity conditions and in Fig. 6e–g under high-humidity conditions. Although the training and test sets were randomly divided such that they did not overlap during dataset classification, a loss of 0% and a classification accuracy of 100% were achieved. This result was observed because the data possessed different characteristics depending on the chemical vapor type and mixing ratio of the chemical vapor composition.

The classification accuracy results for all humidity conditions and mixed gases using the 1D CNN method were 100%, and these classification accuracy results are provided in Tables S4 and S6 for comparison with the machine learning-based feature selection analysis results. Therefore, we confirmed that the 1D CNN algorithm performed much better, with more stable and perfect classification accuracy. According to the results of this evaluation, mixed gas can be classified perfectly without arbitrary feature selection by using the 1D CNN model developed in this study. Therefore, we achieved the development of a deep learning algorithm for mixed gas classification that is more automated and offers greater accuracy compared to machine learning. This algorithm is expected to be the basis for the development of an automatic disease diagnosis system using human exhaled breath in the future.

Furthermore, we additionally verified the discriminative performance of our 1D CNN deep learning on mixed gas-sensing data randomly mixed for low- and high-humidity conditions. Data sensed by our MDFG sensor were used under low and high-humidity conditions for NH3–NO gas mixed at 1:1, 1:3, and 3:1 for deep learning performance verification. Data were randomly shuffled, and the combination of NH3–NO mixed gas was discriminated. As a result, our deep learning achieved 100% test results from the model. We set most conditions of the model to be the same as those of our previous model to target the performance verification of our deep learning model, and the deep learning analysis process and classification results are shown in Fig. 6h. Thus, our 1D CNN model has been shown to be able to classify a combination of mixed gases even under random humidity conditions. As the humidity contained in human exhaled breath and natural surroundings is not constant, this result is very important. Since the aim of this study is to introduce a new device and approach for future investigation and commercial purposes, this result may suggest that this study is one step closer to achieving that objective.

This content was originally published here.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.